The youth of the world

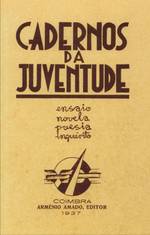

Cadernos da Juventude became a landmark in the cultural and political history of neo-realism even though they were not read by the public, as the magazine was seized before leaving the printer and later destroyed in the courtyard of the Civil Government of Coimbra.

Joaquim Namorado noted the novelty brought by the publication: “it is in the preface to Cadernos da Juventude (...) that the coordinates of neo-realism are presented for the first time as a whole: the defense of a social art, rooted in national realities, that is realistic, anti-subjectivist, and anti-naturalist, whose ideological foundation would be modern rationalism”.

The supressed edition would, therefore, establish the programmatic identity of its authors, young university students moved by the desire to promote a culture in line with the idea of the future that motivated them and the mission that they felt was theirs, both of which went far beyond the explicit intention of Europeanization of the national mental life, as it was the expectation of a new city, one capable of instituting the satisfaction of great human designs, which characterized the demiurgical environment in which they moved.

Under this auspicious light, it seems legitimate to discern in the chosen title – a replica of Les Cahiers de la Jeunesse, which Paul Nizan and Luc Durtain directed since June 1937 – the pressing link that would unite Portuguese intellectuals under the age of thirty with the metaphorical youth of the world raised by the Russian Revolution of October 1917. It should, in fact, be pointed out that the bulletin of the Federation of Portuguese Communist Youths was given, shortly afterward, the same title.

In the published essay, novella, four poems, survey, and two drawings, we find the portrait of a cultural orientation that is sufficiently enlightened and confident to claim a place at the ideological debate, and in the Portuguese letters and arts during the decades that followed. Manuel Filipe argues in favour of the mission of the politically committed intellectual and against the men of culture who supported the autonomous and free use of the spirit. Frederico Alves denounces the misery and suffering of poor peasants. Joaquim Namorado sings the vigour of daily working and factory life. Manuel da Fonseca is moved by the suffering of those who sell their body. Mário Dionísio proclaims the desire to sacrifice himself for a greater purpose. Políbio Gomes dos Santos discusses different modes of human experience and consciousness. The response to the survey on “which ideas in embryology are of most interest to today's youth”, in which Abel Salazar criticizes vitalism, viewed as archaic and metaphysical, and supports neo-positivism and characterology, is laden with the aura of a tutelary figure from the previous generation who distinguished himself by combining civic intransigence and scientific diffusion, as well as expressions of social art.

Cadernos da Juventude also represented an early summary of the organic structuring of the neo-realist movement, not only because they were published in Coimbra, which remained the centre of the new generation’s periodical activity for several decades, but above all because they brought together, in the scarce nine pieces published, which include the drawings of António José Soares and Fernando Namora, a group of authors destined to become some of the movement’s major references, hailing also from Lisbon, Alentejo, and Porto.

Today, it is obvious that the seizure of the Cadernos was an inconsequential gesture, as is typical of those who presume to have the ability to deny others’ profound enthusiasms. Those who were momentarily deprived of the opportunity to read Namorado’s, Dionísio’s, or Políbio’s texts quickly came to find their writings in periodicals such as Sol Nascente, Altitude, O Diabo and, subsequently, Vértice, and soon had at their disposal the printed works of those who had seen the inaugural collective organ consumed by the flames set in the Civil Government, in the Alta of Coimbra, a building itself condemned, a few years later, to fire and ash.

The suppression of Cadernos da Juventude failed, even within the strict limits of its seizure. Some copies – one, two, or three, to existing versions – were removed from the police operation, namely the one that made its way to the Municipal Library of Coimbra, where Carlos Santarém de Andrade took the initiative, half a century later, to publish a facsimile edition in the same printing house and using similar paper.

In the shadowy censorial backstage, another original survived, belonging to the Serviços de Censura à Imprensa, kept in the archives of Palácio Foz.

It is this specimen, in a way unpublished, that we now present, with the comfort of those who exercise the mythical justice attributed to the act of writing History. In this case, the satisfaction of finally making the Cadernos da Juventude universally accessible.

Luís Andrade