Exílio

As Teresa Almeida states in her canonical study of this magazine, Exilio can be said to be a 'project' between Nationalism and Modernism.

The title, Exilio, immediately suggests the same fate of banishment that its publisher, Augusto de Santa-Rita, the more arrière-garde and nostalgist brother of Santa-Rita Pintor, cultivated in his work. The three sonnets (the common traditional form that abounds in Exílio) he decided to include in the publication bring together the Religion-Race pair so often found in many contemporary publications. The titles are significant: ‘Signal of the Race’, ‘Your Presence’, and ‘Heaven’. The great cross of Christ above the graphic part of the title page is also symbolic of this. Côrtes-Rodrigues’ text, a timid Modernist and personal friend of Pessoa, titled ‘Via-Sacra’, follows the same route.

His program was clear, alluded to in the first text, ‘Exílio - Its Justification’, by the editor. Next, we find poems by one of the authors involved in Orpheu, perhaps the least known and most shy of the group, Alfredo Guisado, writing under the pseudonym Pedro de Menezes. These are the sonnets ‘The Fear of Satan at Night’, true symbolist hymns to the Night, containing an allusion to vagueness, and a languid and heavy description commonly found in the texts of the movement. Incidentally, Pedro de Menezes / Alfredo Guisado is mentioned in the last piece of the issue, thereby completing the circle.

This text written by Fernando Pessoa is precisely one of the most important in Exílio. With it, Pessoa develops his sensationist theory, signing ‘Fernando Pessoa, sensationist poet’, and contrasts two works published that year (by Pedro de Menezes and João Cabral do Nascimento, a monarchist and integralist poet from Funchal) stating that, in their own way, both are sensationists.

In fact, the author of Message collaborates here not only as a critic but also as an author. In pages 13-16, he includes one of the most important poems of his first symbolist period, ‘Absurd Hour’, a poem dated 4 July 1913, and therefore written months before the appearance of the heteronyms (March 1914). When it was published, however, Pessoa would already have distanced himself from the text, having started his Paulism theory, the first of the ‘isms’. Sensationism, as we know, was the last ‘ism’ created by the author, c. 1915, following two others – Paulism and Interseccionism – that appeared in the immediately preceding years (c. 1913-14, 1914-15, respectively); Sensationism came to function as an agglutinating ‘ism’ for all three. Therefore, even if we find ourselves before a sensationist poem, the aesthetic and technical affiliation of ‘Absurd Hour’ is closer to Interseccionism – one of its elements.

To go back to the beginning for a moment, it is worth noting that several texts supporting Nationalist ideas were published in this literary magazine: Leite de Vasconcelos, the eminent archaeologist of Etnografia Portuguesa, writes a detailed and thorough article about Portuguese numismatics; Cláudio Basto (also an ethnographer and frequent collaborator of the publication that Leite de Vasconcelos had founded in 1889, Revista Lusitana) writes about the morphology of names, based on parish records from Minho; Teófilo Braga completes the trinity of the illustrious and old intelligentsia, signing a historical piece on the struggles of the Restoration, namely the connection between the Braganças and the Jesuits. It is plain to see that these three articles are paradigmatic of a certain ornamented Nationalism and display a concern with the past.

In this sense, the contribution of António Ferro, another collaborator in Orpheu, shows the presence of a type of traditionalism in the poetry of its time: in Exílio, Ferro publishes quatrains, matching popular taste, with music by David de Souza.

Surprisingly, António Sardinha is also one of Exilio’s authors. This initial bewilderment is dispelled, however, if we consider the magazine’s index and what was previously mentioned: Alberto Monsaraz, another eminent integralist, is the subject of the dedication of ‘Poente de Nero’, a long poem in two parts written by a lesser-known writer (Martinho Nobre de Mello). The piece is a historical invective about the history of the Roman leader, where many thoughts about the recent history of Portugal can be found, in a clear warning to readers.

Despite the magazine’s somewhat arrière-garde content, some texts seem to want to overcome their historic bounds. In addition to the text by Pessoa, the best example of this is the fantastic writing in ‘Memories of a Mirror’, by another unknown writer (António Rita-Martins) and dedicated to Almada Negreiros. Here, the text innovates by its appreciably cinematographic narration, presenting analeptic flashes and images of the life of a mirror as an aesthetical device: resulting in an imaginative and singular text.

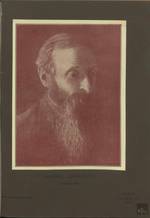

From the visual point of view, Exílio is almost devoid of images. The incipit letter of each article reminds us of medieval illuminations, and the cover, which we have already alluded to, shows a stylized, ancient letter surmounted by the cross of Christ. However, as in other periodicals of its time, clichés were beginning to be considered as a form of illustration. Halfway through Exílio we find an unpublished portrait of Guerra Junqueiro, which also represents a form of legitimation for the magazine. Its author, Victoriano Braga, is also responsible for the theatrical chronicle (p. 44), where an important fact is reported: the inauguration of the Teatro República (now São Luiz) that will serve as the stage, the following year, for Almada and Santa-Rita’s 1st Futurist Conference...

Banishment or exile are thus reasonable words when discussing this magazine. It constitutes a modernist continuation of Orpheu, with the inclusion of texts from the more timid and less innovative collaborators, but also a step backwards, reflecting the taste and the values of its publisher: "Exílio – will finally become the beautiful banished beach where all those who still trust in the resurgence of Portugal by the young will voluntarily remove themselves to, regardless of their political nature."

Ricardo Marques