Misunderstandings of neo-realism

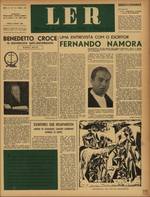

Ler. Jornal de Letras, Artes e Ciências, published monthly by Publicações Europa-América, between April 1952 and October 1953, combined a cultural newspaper attentive to literary and artistic news, a magazine of in-depth articles and criticism, and an editorial bulletin dedicated to listing recent publications (the latter of which determined the publication’s original title).

The intended and implemented orientation strove toward “welcoming all literary and aesthetic currents” and “collecting the collaboration of all truly representative and significant values”, with the purpose of bringing together writers, artists, publishers, and the public.

Readers of the “only literary newspaper that is published among us” can easily observe the cultural life of the period pulsating in its pages. Among regular collaborators we find major men of letters, such as Ferreira de Castro or José Régio, accompanied by a wide range of neo-realist authors, notably Mário Dionísio, Carlos de Oliveira, António Ramos de Almeida, Vergílio Ferreira, António José Saraiva, and Fernando Lopes Graça, together with writers of a very different nature, such as António Quadros, Delfim Santos, José Marinho, Luís de Almeida Braga, and Joaquim Paço d'Arcos.

In addition to literary matters (including an uncommon recognition of female authors), which take up the majority of the periodical, meticulous attention was also given to visual arts, theatre, music, and dance criticism, by such renowned names as Adriano Gusmão, Luís Francisco Rebelo, João de Freitas Branco, or Tomás Ribas. The predominantly French international cultural news proved equally regular and detailed. The “Bibliografia portuguesa” section presented the national editorial movement with a thematic organization. The sciences ended up being the poor relative of the areas mentioned in the subtitle, despite the noteworthy collaboration of Orlando Ribeiro and the translations of scientists like Jean Rostand.

Although the editorial staff proclaimed, over several editorials, the intent of journalistic exemption, outside any specific ideology, the publication’s content was clearly within the scope of progressive cultural references, from Victor Hugo to Jorge Amado, despite having also published opposing texts, such as the praise of António Macedo de Papança, Count of Monsaraz, and the Integralist literary salon that he organized in the Coimbra Alta.

At the origin of Ler were Francisco Lyon de Castro, owner, along with his brother Adelino, of the Publicações Europa-América, and Fernando Piteira Santos, who was a literary advisor at the publisher. Both had left the Portuguese Communist Party, under accusations of Titoism, among other anathemas, while at the same time remaining firm oppositionists to the Salazarist order, namely in terms of cultural confrontation and the dissemination of knowledge.

To recognize Piteira Santos as the craftsman of Ler is a given. On one hand, he had already performed a similar job during the final stage of the weekly periodical O Diabo, which meant he had an accurate knowledge of the journalistic profession and an intimate perception of the national literary and artistic environment. On the other hand, a desire to lead was one of the most salient traits in his personality, as evidenced both by his past endeavours, in the Communist Party and the Movimento de Unidade Democrática, and in his later trajectory, as leader of the Frente Patriótica de Libertação Nacional.

Despite the modest stated purposes of an ordinary literary periodical, Ler eventually took up a very relevant position in the political-cultural trajectory of neo-realism, by exposing the equivocal core of a literary movement that was more rooted in ideological and political assumptions than in artistic orientations or aesthetics.

As Pacheco Pereira pointed out, the international political context of confrontation between the two blocs that had emerged from World War II, which were clashing in Korea, and the particularly violent repression unleashed by Salazarism after the 1949 presidential elections contributed to the radicalization of positions that rejected the broad and inclusive front promoted by the publication.

On the other hand, according to João Madeira, the consolidation of a strictly cultural periodical directed by communist dissidents who were capable of bringing together intellectuals with Marxist tendencies would constitute, in itself, a political gesture of heterodox detachment.

Simultaneously, many of the articles published by neo-realist authors dealt with specific aspects of literary and artistic work, regarding their nature and merit. As such, they picked sides in the latent conflict that ran through the movement by focusing their reflections on the “interior of the laboratory” of letters and colours, as with Mário Dionísio, or on the “praise of style”, as in Carlos de Oliveira’s texts. In both authors, this came with the indictment of “a certain theorization that heedlessly postulated the repudiation of form” and that “demanded that every novel, every poem, shouted truths like fists”.

These articles certainly contributed to quickly moving the answer to the concerns put forth, seen as similar to those of the spurned “formalism” and distant from pertinent social and political contents, from underground to frontal discussion, by opening the door to a long and lively polemic among neo-realists, of which the article “Humanismo e ciência”, published by António José Saraiva in the second issue of Ler, was an important part.

A third conflict front between neo-realists, still during the brief nineteen months in which Francisco Lyon de Castro’s and Fernando Piteira Santos’ periodical was published, was triggered by the Letter of the “Friends of Vertice”, dated August 25, 1952. It questioned the orientation of the magazine that provided the movement’s public expression and sought to change its directive structure.

As for official party reactions, Ler was denounced and repudiated in Avante!, in an article entitled “’Ler’ serve os objectivos do fascismo. Lutemos contra a penetração ideológica americana!”, in communiqués from the communist regional directorates of Lisbon and the North, and in letters of intimation addressed to collaborators of the periodical, namely Mário Dionísio, João José Cochofel, and Fernando Lopes Graça.

As this brief overview illustrates, the role that Ler played in the history of neo-realism was not a result of the originality of the questions posed in its pages, but rather consisted, above all, in bringing the movement's programmatic ambiguities to the condition of paradoxical aporias: a literary and artistic movement that lacked a defined aesthetic purpose, consequently forcing the recapitulation of basic considerations on working with words, shapes, and colours; a cultural current subjected to the invocation of “useful art” contrasting representations about its value, from vague ideological insinuation to explicit political combat literature; a discourse supported by the double language of party and political convergence that ranges from simple request of writers’ social responsibility to the intransigence of orthodox diktat.

It should be said that this equivocity goes back to the very definition of socialist realism, an expression with dissonant terms, as can easily be seen in Aragon's Pour um Réalisme Socialiste, which, notwithstanding, was a source of inspiration for Joaquim Namorado, the Marxist writer from Coimbra who coined the term “neo-realism”.

When, in the final issue of Ler, critic José Pedro de Andrade discusses the stylistic questions raised by Uma Abelha na Chuva, by Carlos de Oliveira, whose publication had been announced two months prior, we see that the arguments discussed in the periodical exceed the simple discursive plane, as they are clearly reflected in the published literary production. On the other hand, if we consider that Álvaro Cunhal’s prison drawings are from the same period it becomes evident that neo-realism constitutes a sufficiently fractured literary and artistic current that even the author of Até amanhã, camaradas, who was among its founders and lifelong supporters, including in the cited polemic, is rarely mentioned as a canonical author.

Therefore, the split that occurred in relation to Ler, which originated the “purge of intellectuals”, made it clear that a single neo-realism never existed, but rather many, in view of such different conceptions and works.

Inside a movement that never failed to consider the construction of its own memory as a fundamental part of its ideological identity, this dissent extended different and contradictory identity representations that were consolidated over decades; some of these were more literary and artistic while others more intent on fighting for political content and pragmatics.

The return to Ler, to the content, history, and circumstances surrounding the monthly periodical, now allows each of its current readers to directly access both the perception of the syncretic complexity of the difficult combination of revolutionary letters, art, and politics, and the concrete terms and occurrences of the threads from which new realism was woven.

Luís Andrade