Portugal Futurista

‘The boys of my time! And never in Portugal were the boys more

boys than the ones I met and cherished in 1917, at Cafe Martinho,

because none could achieve the belief in their own youth as they did. In

1917, we believed in ourselves, in our voluptuous and optimistic youth.

It was a patriotic duty to be a young man. Ageing Portugal – to

rejuvenate itself needed the staunch and sincere youth of boys. And we,

for the sake of patriotism, not only wanted to rejuvenate Portugal with

our youth, we also wanted to make Lisbon the head of Europe. And the

youth of that time, who had already launched a few modernist magazines –

amazed the Portuguese public with a magazine that exceeded in audacity

and originality all that had hitherto been published. It was

Portugal Futurista.‘

(Rebelo de Bettencourt, O Mundo das Imagens, Lisboa,

Ressurgimento)

Rebelo de Bettencourt thus celebrates the context of the emergence of Portugal Futurista, in one of the rare personal testimonials about this now mythical magazine that have survived.

Portugal Futurista was not, in fact, like any other magazine. Despite – et pour cause – its single issue, the immediate apprehension it was subjected to is truly indicative of the content, as unusual as that of Orpheu two years earlier, and which even today makes us smile. There is even a letter, dated 11 July 1917, which shows continuity between the two magazines, different protagonists notwithstanding. The author of the letter, Fernando Pessoa, discusses the possibility of publishing a third issue of Orpheu, something which, as we know, did not happen in his lifetime. Moreover, it is Pessoa himself who can be found in the midst of both the continuity and the split this magazine represents: if on one hand he signs a poems with his own name (‘Episódios’ and ‘Ficções do Interlúdio’), both at odds with what we could consider 'futurist', he also publishes, via the Álvaro de Campos heteronym, the 'Ultimatum' manifesto, also presented in a curious offprint that calls into question the commonly accepted date of the magazine itself (at the end of the text, we are told that ‘Saudação a Walt Whitman’ would appear in October 1917 in Orpheu 3...).

In fact, given the lack of publicity prior to the appearance of the magazine, it is only through an astral chart drawn by Pessoa (currently in his archive at the BNP) that we are aware of the launch (and sale of the first issue at 9 a.m., 31 October) and apprehension dates (2 November). Even to this day, much has been speculated about these dates, since the apprehension order has not yet been found. The chart is the only document that provides a possible date, and clarifies that, contrary to what was previously believed, the apprehension did not take place at the typographer’s workshop.

The internal complexity of this unique issue can be seen in the two insert pages, one for the promotion of the ‘Russian Ballets’/’Bailados Russos’ – that were due to arrive in Lisbon in December – and another to publicize the work, appearing in the following fifteen days, by one of the authors who represents a central axis of the magazine: A Engomadeira, by Almada Negreiros. Three variants of the leaflet ‘A Engomadeira’ are also known, as seen in the commemorative exhibition for the magazine’s centennial (BNP, 2017). As for ‘Bailados Russos’, although the text is signed by three people – Almada, Ruy Coelho, and José Pacheco – we know that Almada was the only one who wrote it, as early as October 1917, when there was still talk of the arrival of the Russian Ballets in Lisbon, and even though the writer had not actually seen them live (they would arrive in Lisbon between December of that year and January 1918, having performed 11 shows in total).

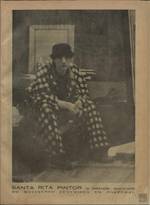

On the other hand, the publication of this magazine should also be linked to another (futurist) 1917 event: the 1st Futurist Conference, organized by Almada and Santa-Rita in the recently inaugurated Teatro República (now São Luiz), in Lisbon. Not only does the program of the conference appear in Portugal Futurista, but we also have the complete reproduction of the manifestos read in April on the pages of the magazine: Manifesto of Music-Hall (by Marinetti, 1913), Manifesto of Lust (by Valentine Saint-Point), and the Futurist Manifesto to the Portuguese Generations of the 20th Century (written by Almada specifically for the conference).

We need to bear in mind that one of the peculiarities of Portugal Futurista is its connection to another publication, O Heraldo, published in Faro. This periodical (also encouraged by the bombastic novelty that Orpheu represented in 1915) sought to promote the futurist movement, publishing a section, from the end of 1916, containing futurist texts, signed by creative pseudonyms. It is through this newspaper that we find out, in a letter by Santa-Rita Pintor and Almada Negreiros (the so-called 'Futurist Committee') dated 5 August 1917, that this futurist magazine would appear briefly. Sadly, however, O Heraldo would end in two weeks-time and would live to see the appearance of Portugal Futurista in October.

An unrepeatable magazine, an editorial enigma, a shake-up in times of war and religious apparitions, Portugal Futurista was, in short, an insurrectional attempt of a group of enlightened youths, united in their diversity to introduce Portugal in the literary and artistic 20th century.

Ricardo Marques