Sphinx

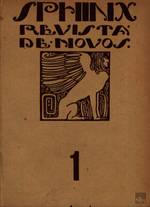

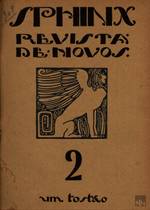

Sphinx is a ‘magazine of the young’, as its subtitle reads. Two issues were published, both in 1917. Its editorial board was split between the literary directors, Laura Nogueira and Celestino Soares, and the artistic directors, Leitão de Barros and Cottinelli Telmo, who were then in their early twenties.

Celestino Soares presents the magazine, in the first pages of the inaugural issue (February 1917), with the following words:

‘Our magazine is therefore one of many attempts for the Emancipation of theS pirit, that Civilization and Schools have transformed, in order to make the man of today – an 'antihuman creature, without beauty, without strength, without freedom , without laughter, without feeling, and carrying a spirit that is passive as a slave or impudent as a jester’, so that 'all, intellectually, are but sheep walking the same path, bleating the same bleat, snout pointed at the dust where well-trodden footprints are repeatedly stepped on.’

In Sphinx we feel at first a proud (though perhaps insipid) desire to do things differently, and even the way of looking at the magazine as an object conforms to a notion of these periodicals that spread in the 20s: a set of literary sheets, always featuring illustrations with each text (therefore different from Orpheu, Exílio, or Centauro), and, mainly, with advertisements. It may be interesting to note that some of these ads promote other people in the established literary milieu. Here, Ana de Castro Osório’s Casa Editora ‘Para as Crianças’, stands out. Her brother, in fact, is a contributor to the second issue, with a poem.

Another way to be 'different' is to pay attention to what is happening outside Portugal. In a small note which closes the first issue, someone with the pseudonym 'Sphinx of Hellas'(Esfinge da Hélade) (perhaps editor Luís de Almeida Nogueira, if we look at the signature in the second issue) writes a column and a half about the disappearance of 'an aesthete': none other than vorticist sculptor Gaudier-Bzerska, a member of the English modernist movement, that was headed by Wyndham Lewis and had published the magazine Blast (of which both Sá-Carneiro and Pessoa had a copy) in the same year as Orpheu.

As far as Sphinx's artistic contribution is concerned, the beautiful mythical creature drawn on the cover, much to the taste of the 10s, and certainly created by one of the artistic directors, is emblematic of a carefully crafted magazine. The literary contributions are far from innovative, featuring names such as João Cabral do Nascimento, Américo Durão – and even a review, in the second issue, of what seems to have been an important book in 1917 (if we look at other periodicals): Charcos, by Alfredo de Freitas Branco, the chief editor of the first issue of A Tradição.

On the other hand, the appearance of Sphinx created some interest in other publications, perhaps because of the connections between these illustrious youths and some powerful families. As an example, Algarve’s O Heraldo, in its third and final series, when it was already publishing the ‘Gente Nova’ section featuring futurist texts, not only reports the appearance of Sphinx’s second issue (March 1917), but also contains a reference to the magazine in an article by one of the new futurist authors (O Heraldo, nr. 382, 20 May 1917). This connection can also be found in the second issue of Sphinx, were we find a reference to O Heraldo (p. 47). Also relevant is Terra Portuguesa, a periodical that was subtitled ‘Illustrated Magazine of Archeology and Ethnography’ (directed by art historian Virgílio Correia, who was also a member of Atlântida’s directorial board, which ran between 1916 and 1927) whose advertisement appears on the second page of the first issue.

The ‘Novíssimos’ section, within a ‘magazine of the young', aims to enumerate names from the (then) new generation that should be remembered. In the first issue, artistic director Leitão de Barros is not shy in writing about the talent of his colleague Cottinelli Telmo; Helena Roque Gameiro (they would marry in 1923) is also referred to as a promising talent, and in another page of the same issue it is her sister, Raquel Gameiro Ottolini, that shares a maritime illustration (p. 12) alongside a bucolic poem by Teresa Leitão de Barros.

It is plain to see how this is a publication by young people wanting to break with the past, but still very much attached to nationalisms and passé ideas of different kinds, both because of their discourse and their extra-literary links with other publications and their protagonists. Notwithstanding, it is a very uniquely designed magazine and provides a glimpse into the typical literary periodical of the following decade, containing advertisements and illustrations.

Ricardo Marques